Tutorial: Web Scraping with Python Using Beautiful Soup

Learn how to scrape the web with Python!

The internet is an absolutely massive source of data — data that we can access using web scraping and Python!

In fact, web scraping is often the only way we can access data. There is a lot of information out there that isn’t available in convenient CSV exports or easy-to-connect APIs. And websites themselves are often valuable sources of data — consider, for example, the kinds of analysis you could do if you could download every post on a web forum.

To access those sorts of on-page datasets, we’ll have to use web scraping.

Don’t worry if you’re still a total beginner!

In this tutorial we’re going to cover how to do web scraping with Python from scratch, starting with some answers to frequently-asked questions.

Then, we’ll work through an actual web scraping project, focusing on weather data.

We’ll work together to scrape weather data from the web to support a weather app.

But before we start writing any Python, we’ve got to cover the basics! If you’re already familiar with the concept of web scraping, feel free to scroll past these questions and jump right into the tutorial!

The Fundamentals of Web Scraping:

What is Web Scraping in Python?

Some websites offer data sets that are downloadable in CSV format, or accessible via an Application Programming Interface (API). But many websites with useful data don’t offer these convenient options.

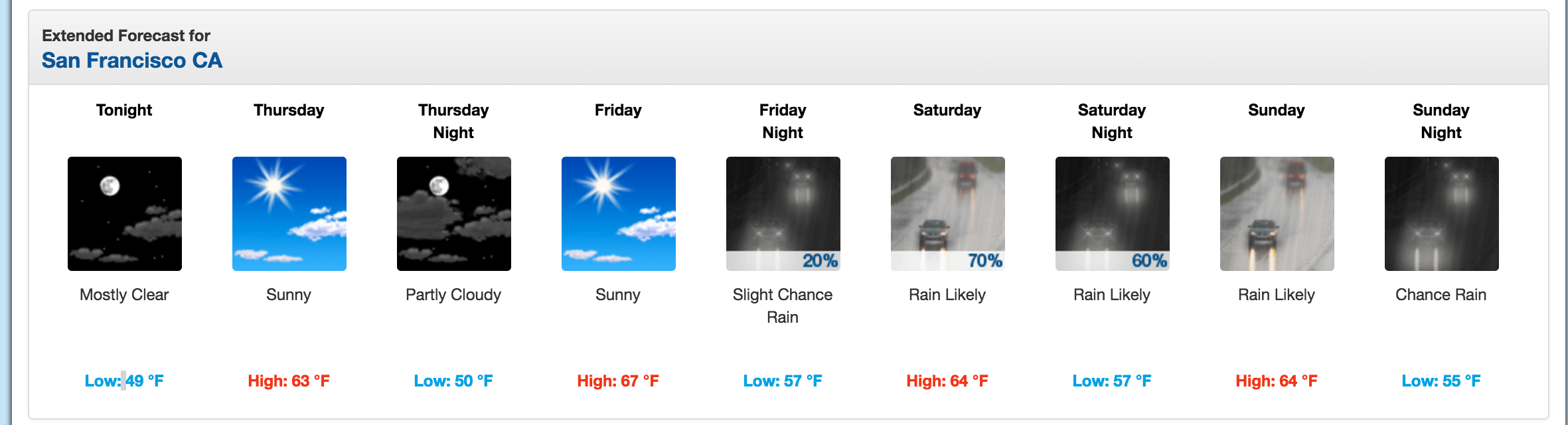

Consider, for example, the National Weather Service’s website. It contains up-to-date weather forecasts for every location in the US, but that weather data isn’t accessible as a CSV or via API. It has to be viewed on the NWS site:

If we wanted to analyze this data, or download it for use in some other app, we wouldn’t want to painstakingly copy-paste everything. Web scraping is a technique that lets us use programming to do the heavy lifting. We’ll write some code that looks at the NWS site, grabs just the data we want to work with, and outputs it in the format we need.

In this tutorial, we’ll show you how to perform web scraping using Python 3 and the Beautiful Soup library. We’ll be scraping weather forecasts from the National Weather Service, and then analyzing them using the Pandas library.

But to be clear, lots of programming languages can be used to scrape the web! We also teach web scraping in R, for example. For this tutorial, though, we’ll be sticking with Python.

How Does Web Scraping Work?

When we scrape the web, we write code that sends a request to the server that’s hosting the page we specified. The server will return the source code — HTML, mostly — for the page (or pages) we requested.

So far, we’re essentially doing the same thing a web browser does — sending a server request with a specific URL and asking the server to return the code for that page.

But unlike a web browser, our web scraping code won’t interpret the page’s source code and display the page visually. Instead, we’ll write some custom code that filters through the page’s source code looking for specific elements we’ve specified, and extracting whatever content we’ve instructed it to extract.

For example, if we wanted to get all of the data from inside a table that was displayed on a web page, our code would be written to go through these steps in sequence:

- Request the content (source code) of a specific URL from the server

- Download the content that is returned

- Identify the elements of the page that are part of the table we want

- Extract and (if necessary) reformat those elements into a dataset we can analyze or use in whatever way we require.

If that all sounds very complicated, don’t worry! Python and Beautiful Soup have built-in features designed to make this relatively straightforward.

One thing that’s important to note: from a server’s perspective, requesting a page via web scraping is the same as loading it in a web browser. When we use code to submit these requests, we might be “loading” pages much faster than a regular user, and thus quickly eating up the website owner’s server resources.

Why Use Python for Web Scraping?

As previously mentioned, it’s possible to do web scraping with many programming languages.

However, one of the most popular approaches is to use Python and the Beautiful Soup library, as we’ll do in this tutorial.

Learning to do this with Python will mean that there are lots of tutorials, how-to videos, and bits of example code out there to help you deepen your knowledge once you’ve mastered the Beautiful Soup basics.

Is Web Scraping Legal?

Unfortunately, there’s not a cut-and-dry answer here. Some websites explicitly allow web scraping. Others explicitly forbid it. Many websites don’t offer any clear guidance one way or the other.

Before scraping any website, we should look for a terms and conditions page to see if there are explicit rules about scraping. If there are, we should follow them. If there are not, then it becomes more of a judgement call.

Remember, though, that web scraping consumes server resources for the host website. If we’re just scraping one page once, that isn’t going to cause a problem. But if our code is scraping 1,000 pages once every ten minutes, that could quickly get expensive for the website owner.

Thus, in addition to following any and all explicit rules about web scraping posted on the site, it’s also a good idea to follow these best practices:

Web Scraping Best Practices:

- Never scrape more frequently than you need to.

- Consider caching the content you scrape so that it’s only downloaded once.

- Build pauses into your code using functions like

time.sleep()to keep from overwhelming servers with too many requests too quickly.

In our case for this tutorial, the NWS’s data is public domain and its terms do not forbid web scraping, so we’re in the clear to proceed.

Learn Python the Right Way.

Learn Python by writing Python code from day one, right in your browser window. It's the best way to learn Python — see for yourself with one of our 60+ free lessons.

The Components of a Web Page

Before we start writing code, we need to understand a little bit about the structure of a web page. We’ll use the site’s structure to write code that gets us the data we want to scrape, so understanding that structure is an important first step for any web scraping project.

When we visit a web page, our web browser makes a request to a web server. This request is called a GET request, since we’re getting files from the server. The server then sends back files that tell our browser how to render the page for us. These files will typically include:

- HTML — the main content of the page.

- CSS — used to add styling to make the page look nicer.

- JS — Javascript files add interactivity to web pages.

- Images — image formats, such as JPG and PNG, allow web pages to show pictures.

After our browser receives all the files, it renders the page and displays it to us.

There’s a lot that happens behind the scenes to render a page nicely, but we don’t need to worry about most of it when we’re web scraping. When we perform web scraping, we’re interested in the main content of the web page, so we look primarily at the HTML.

HTML

HyperText Markup Language (HTML) is the language that web pages are created in. HTML isn’t a programming language, like Python, though. It’s a markup language that tells a browser how to display content.

HTML has many functions that are similar to what you might find in a word processor like Microsoft Word — it can make text bold, create paragraphs, and so on.

If you’re already familiar with HTML, feel free to jump to the next section of this tutorial. Otherwise, let’s take a quick tour through HTML so we know enough to scrape effectively.

HTML consists of elements called tags. The most basic tag is the <html> tag. This tag tells the web browser that everything inside of it is HTML. We can make a simple HTML document just using this tag:

<html>

</html>We haven’t added any content to our page yet, so if we viewed our HTML document in a web browser, we wouldn’t see anything:

Right inside an html tag, we can put two other tags: the head tag, and the body tag.

The main content of the web page goes into the body tag. The head tag contains data about the title of the page, and other information that generally isn’t useful in web scraping:

<html>

<head>

</head>

<body>

</body>

</html>We still haven’t added any content to our page (that goes inside the body tag), so if we open this HTML file in a browser, we still won’t see anything:

You may have noticed above that we put the head and body tags inside the html tag. In HTML, tags are nested, and can go inside other tags.

We’ll now add our first content to the page, inside a p tag. The p tag defines a paragraph, and any text inside the tag is shown as a separate paragraph:

<html>

<head>

</head>

<body>

<p>

Here's a paragraph of text!

</p>

<p>

Here's a second paragraph of text!

</p>

</body>

</html>Rendered in a browser, that HTML file will look like this:

Here’s a paragraph of text!

Here’s a second paragraph of text!

Tags have commonly used names that depend on their position in relation to other tags:

child— a child is a tag inside another tag. So the twoptags above are both children of thebodytag.parent— a parent is the tag another tag is inside. Above, thehtmltag is the parent of thebodytag.sibiling— a sibiling is a tag that is nested inside the same parent as another tag. For example,headandbodyare siblings, since they’re both insidehtml. Bothptags are siblings, since they’re both insidebody.

We can also add properties to HTML tags that change their behavior. Below, we’ll add some extra text and hyperlinks using the a tag.

<html>

<head>

</head>

<body>

<p>

Here's a paragraph of text!

<a href="https://www.dataquest.io">Learn Data Science Online</a>

</p>

<p>

Here's a second paragraph of text!

<a href="https://www.python.org">Python</a> </p>

</body></html>Here’s how this will look:

Here’s a paragraph of text! Learn Data Science Online

Here’s a second paragraph of text! Python

In the above example, we added two a tags. a tags are links, and tell the browser to render a link to another web page. The href property of the tag determines where the link goes.

a and p are extremely common html tags. Here are a few others:

div— indicates a division, or area, of the page.b— bolds any text inside.i— italicizes any text inside.table— creates a table.form— creates an input form.

For a full list of tags, look here.

Before we move into actual web scraping, let’s learn about the class and id properties. These special properties give HTML elements names, and make them easier to interact with when we’re scraping.

One element can have multiple classes, and a class can be shared between elements. Each element can only have one id, and an id can only be used once on a page. Classes and ids are optional, and not all elements will have them.

We can add classes and ids to our example:

<html>

<head>

</head>

<body>

<p class="bold-paragraph">

Here's a paragraph of text!

<a href="https://www.dataquest.io" id="learn-link">Learn Data Science Online</a>

</p>

<p class="bold-paragraph extra-large">

Here's a second paragraph of text!

<a href="https://www.python.org" class="extra-large">Python</a>

</p>

</body>

</html>Here’s how this will look:

Here’s a paragraph of text! Learn Data Science Online

Here’s a second paragraph of text! Python

As you can see, adding classes and ids doesn’t change how the tags are rendered at all.

The requests library

Now that we understand the structure of a web page, it’s time to get into the fun part: scraping the content we want!

The first thing we’ll need to do to scrape a web page is to download the page. We can download pages using the Python requests library.

The requests library will make a GET request to a web server, which will download the HTML contents of a given web page for us. There are several different types of requests we can make using requests, of which GET is just one. If you want to learn more, check out our API tutorial.

Let’s try downloading a simple sample website, https://dataquestio.github.io/web-scraping-pages/simple.html.

We’ll need to first import the requests library, and then download the page using the requests.get method:

import requests

page = requests.get("https://dataquestio.github.io/web-scraping-pages/simple.html")

page<Response [200]>After running our request, we get a Response object. This object has a status_code property, which indicates if the page was downloaded successfully:

page.status_code200A status_code of 200 means that the page downloaded successfully. We won’t fully dive into status codes here, but a status code starting with a 2 generally indicates success, and a code starting with a 4 or a 5 indicates an error.

We can print out the HTML content of the page using the content property:

page.content<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>A simple example page</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>Here is some simple content for this page.</p>

</body>

</html>Parsing a page with BeautifulSoup

As you can see above, we now have downloaded an HTML document.

We can use the BeautifulSoup library to parse this document, and extract the text from the p tag.

We first have to import the library, and create an instance of the BeautifulSoup class to parse our document:

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

soup = BeautifulSoup(page.content, 'html.parser')We can now print out the HTML content of the page, formatted nicely, using the prettify method on the BeautifulSoup object.

print(soup.prettify())<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>A simple example page</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>Here is some simple content for this page.</p>

</body>

</html>This step isn’t strictly necessary, and we won’t always bother with it, but it can be helpful to look at prettified HTML to make the structure of the and where tags are nested easier to see.

As all the tags are nested, we can move through the structure one level at a time. We can first select all the elements at the top level of the page using the children property of soup.

Note that children returns a list generator, so we need to call the list function on it:

list(soup.children)['html', 'n', <html> <head> <title>A simple example page</title> </head> <body> <p>Here is some simple content for this page.</p> </body> </html>]The above tells us that there are two tags at the top level of the page — the initial <!DOCTYPE html> tag, and the <html> tag. There is a newline character (n) in the list as well. Let’s see what the type of each element in the list is:

[type(item) for item in list(soup.children)][bs4.element.Doctype, bs4.element.NavigableString, bs4.element.Tag]As we can see, all of the items are BeautifulSoup objects:

- The first is a

Doctypeobject, which contains information about the type of the document. - The second is a

NavigableString, which represents text found in the HTML document. - The final item is a

Tagobject, which contains other nested tags.

The most important object type, and the one we’ll deal with most often, is the Tag object.

The Tag object allows us to navigate through an HTML document, and extract other tags and text. You can learn more about the various BeautifulSoup objects here.

We can now select the html tag and its children by taking the third item in the list:

html = list(soup.children)[2]Each item in the list returned by the children property is also a BeautifulSoup object, so we can also call the children method on html.

Now, we can find the children inside the html tag:

list(html.children)['n', <head> <title>A simple example page</title> </head>, 'n', <body> <p>Here is some simple content for this page.</p> </body>, 'n']As we can see above, there are two tags here, head, and body. We want to extract the text inside the p tag, so we’ll dive into the body:

body = list(html.children)[3]Now, we can get the p tag by finding the children of the body tag:

list(body.children)['n', <p>Here is some simple content for this page.</p>, 'n']We can now isolate the p tag:

p = list(body.children)[1]Once we’ve isolated the tag, we can use the get_text method to extract all of the text inside the tag:

p.get_text()'Here is some simple content for this page.'Finding all instances of a tag at once

What we did above was useful for figuring out how to navigate a page, but it took a lot of commands to do something fairly simple.

If we want to extract a single tag, we can instead use the find_all method, which will find all the instances of a tag on a page.

soup = BeautifulSoup(page.content, 'html.parser')

soup.find_all('p')[<p>Here is some simple content for this page.</p>]Note that find_all returns a list, so we’ll have to loop through, or use list indexing, it to extract text:

soup.find_all('p')[0].get_text()'Here is some simple content for this page.'f you instead only want to find the first instance of a tag, you can use the find method, which will return a single BeautifulSoup object:

soup.find('p')<p>Here is some simple content for this page.</p>Searching for tags by class and id

We introduced classes and ids earlier, but it probably wasn’t clear why they were useful.

Classes and ids are used by CSS to determine which HTML elements to apply certain styles to. But when we’re scraping, we can also use them to specify the elements we want to scrape.

To illustrate this principle, we’ll work with the following page:

<html>

<head>

<title>A simple example page</title>

</head>

<body>

<div>

<p class="inner-text first-item" id="first">

First paragraph.

</p>

<p class="inner-text">

Second paragraph.

</p>

</div>

<p class="outer-text first-item" id="second">

<b>

First outer paragraph.

</b>

</p>

<p class="outer-text">

<b>

Second outer paragraph.

</b>

</p>

</body>

</html>We can access the above document at the URL https://dataquestio.github.io/web-scraping-pages/ids_and_classes.html.

Let’s first download the page and create a BeautifulSoup object:

page = requests.get("https://dataquestio.github.io/web-scraping-pages/ids_and_classes.html")

soup = BeautifulSoup(page.content, 'html.parser')

soup<html>

<head>

<title>A simple example page

</title>

</head>

<body>

<div>

<p class="inner-text first-item" id="first">

First paragraph.

</p><p class="inner-text">

Second paragraph.

</p></div>

<p class="outer-text first-item" id="second"><b>

First outer paragraph.

</b></p><p class="outer-text"><b>

Second outer paragraph.

</b>

</p>

</body>

</html>Now, we can use the find_all method to search for items by class or by id. In the below example, we’ll search for any p tag that has the class outer-text:

soup.find_all('p', class_='outer-text')[<p class="outer-text first-item" id="second"> <b> First outer paragraph. </b> </p>, <p class="outer-text"> <b> Second outer paragraph. </b> </p>]In the below example, we’ll look for any tag that has the class outer-text:

soup.find_all(class_="outer-text")<p class="outer-text first-item" id="second">

<b>

First outer paragraph.

</b>

</p>, <p class="outer-text">

<b>

Second outer paragraph.

</b>

</p>]We can also search for elements by id:

soup.find_all(id="first")[<p class="inner-text first-item" id="first">

First paragraph.

</p>]Using CSS Selectors

We can also search for items using CSS selectors. These selectors are how the CSS language allows developers to specify HTML tags to style. Here are some examples:

p a— finds allatags inside of aptag.body p a— finds allatags inside of aptag inside of abodytag.html body— finds allbodytags inside of anhtmltag.p.outer-text— finds allptags with a class ofouter-text.p#first— finds allptags with an id offirst.body p.outer-text— finds anyptags with a class ofouter-textinside of abodytag.

You can learn more about CSS selectors here.

BeautifulSoup objects support searching a page via CSS selectors using the select method. We can use CSS selectors to find all the p tags in our page that are inside of a div like this:

soup.select("div p")[<p class="inner-text first-item" id="first">

First paragraph.

</p>, <p class="inner-text">

Second paragraph.

</p>]Note that the select method above returns a list of BeautifulSoup objects, just like find and find_all.

Downloading weather data

We now know enough to proceed with extracting information about the local weather from the National Weather Service website!

The first step is to find the page we want to scrape. We’ll extract weather information about downtown San Francisco from this page.

Specifically, let’s extract data about the extended forecast.

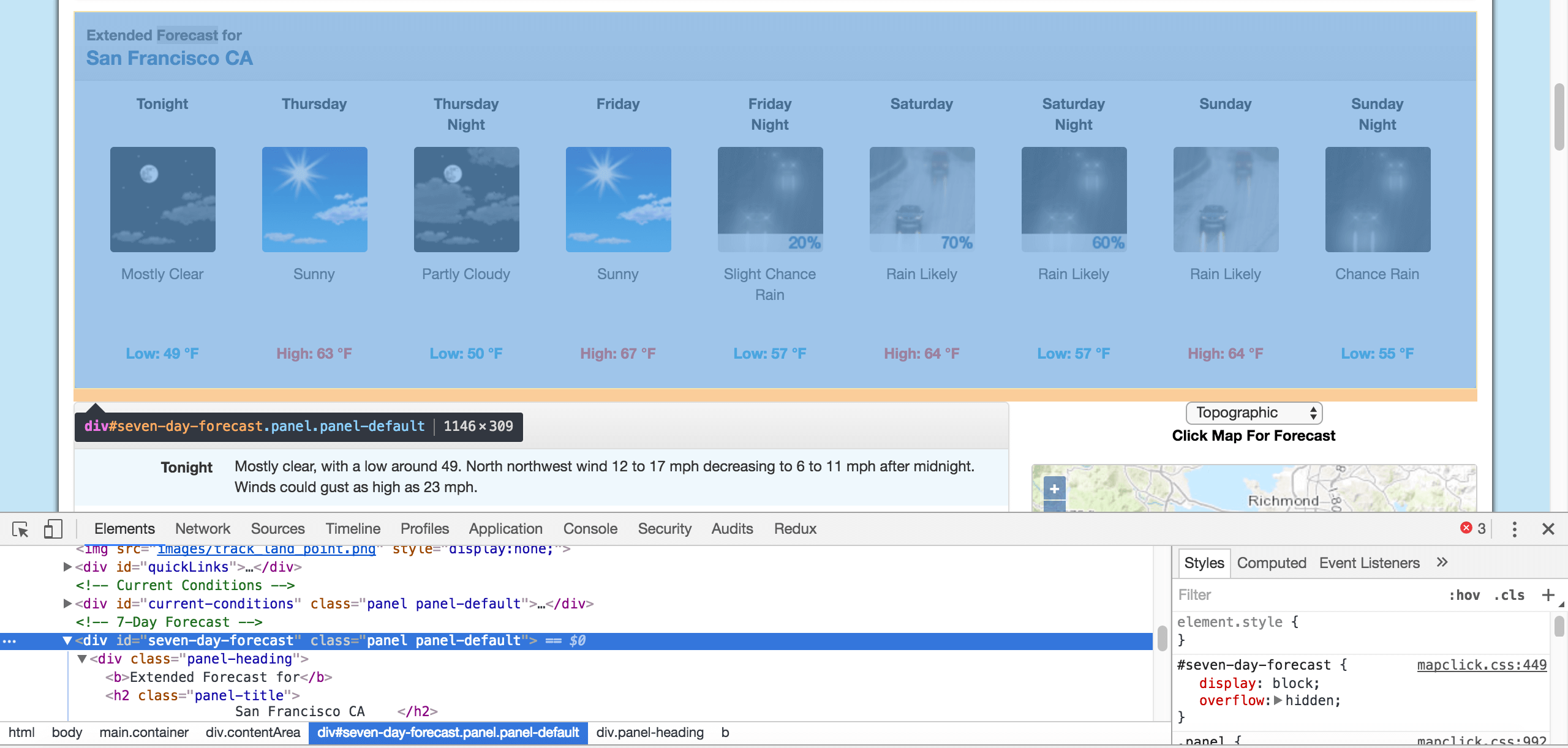

As we can see from the image, the page has information about the extended forecast for the next week, including time of day, temperature, and a brief description of the conditions.

Exploring page structure with Chrome DevTools

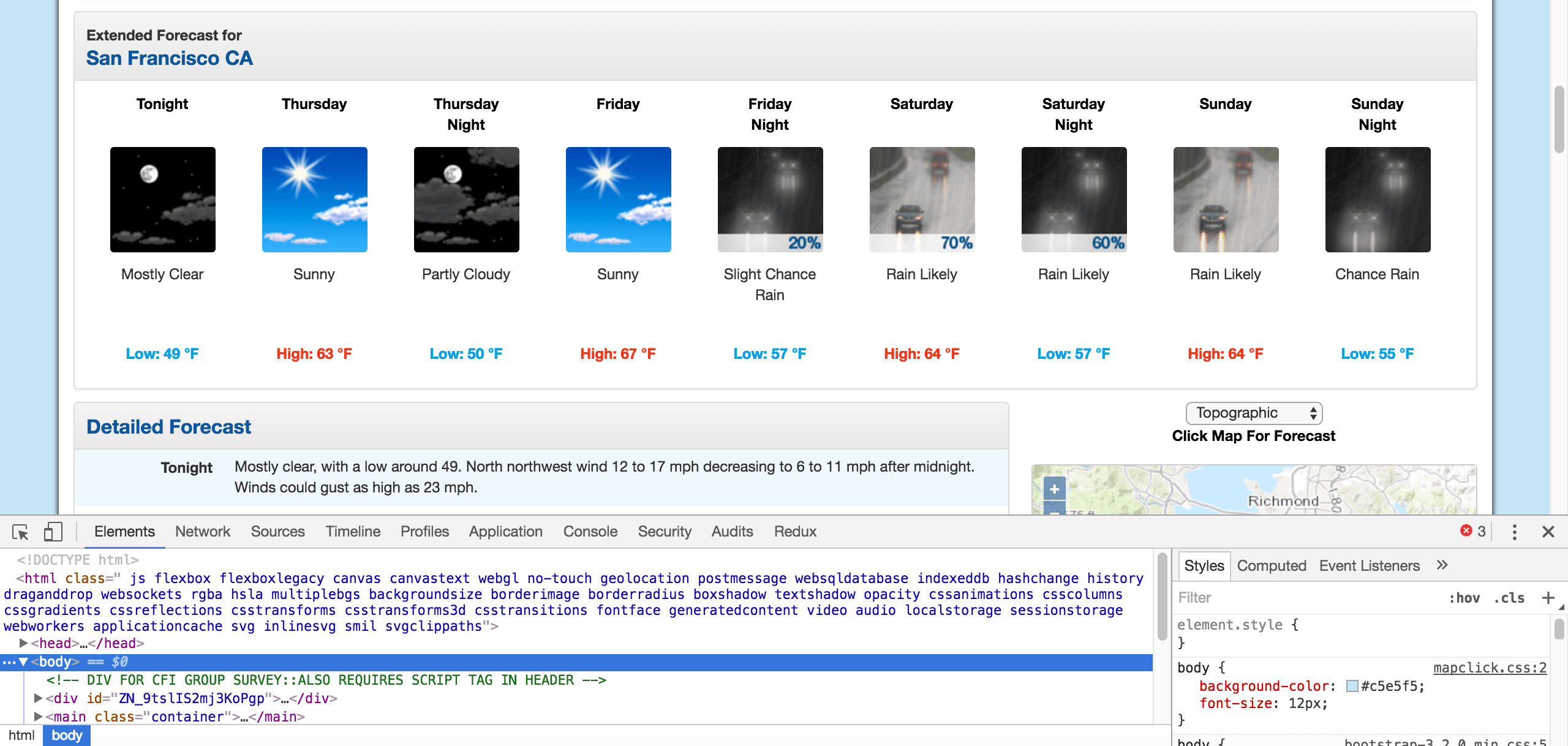

The first thing we’ll need to do is inspect the page using Chrome Devtools. If you’re using another browser, Firefox and Safari have equivalents.

You can start the developer tools in Chrome by clicking View -> Developer -> Developer Tools. You should end up with a panel at the bottom of the browser like what you see below. Make sure the Elements panel is highlighted:

Chrome Developer Tools

The elements panel will show you all the HTML tags on the page, and let you navigate through them. It’s a really handy feature!

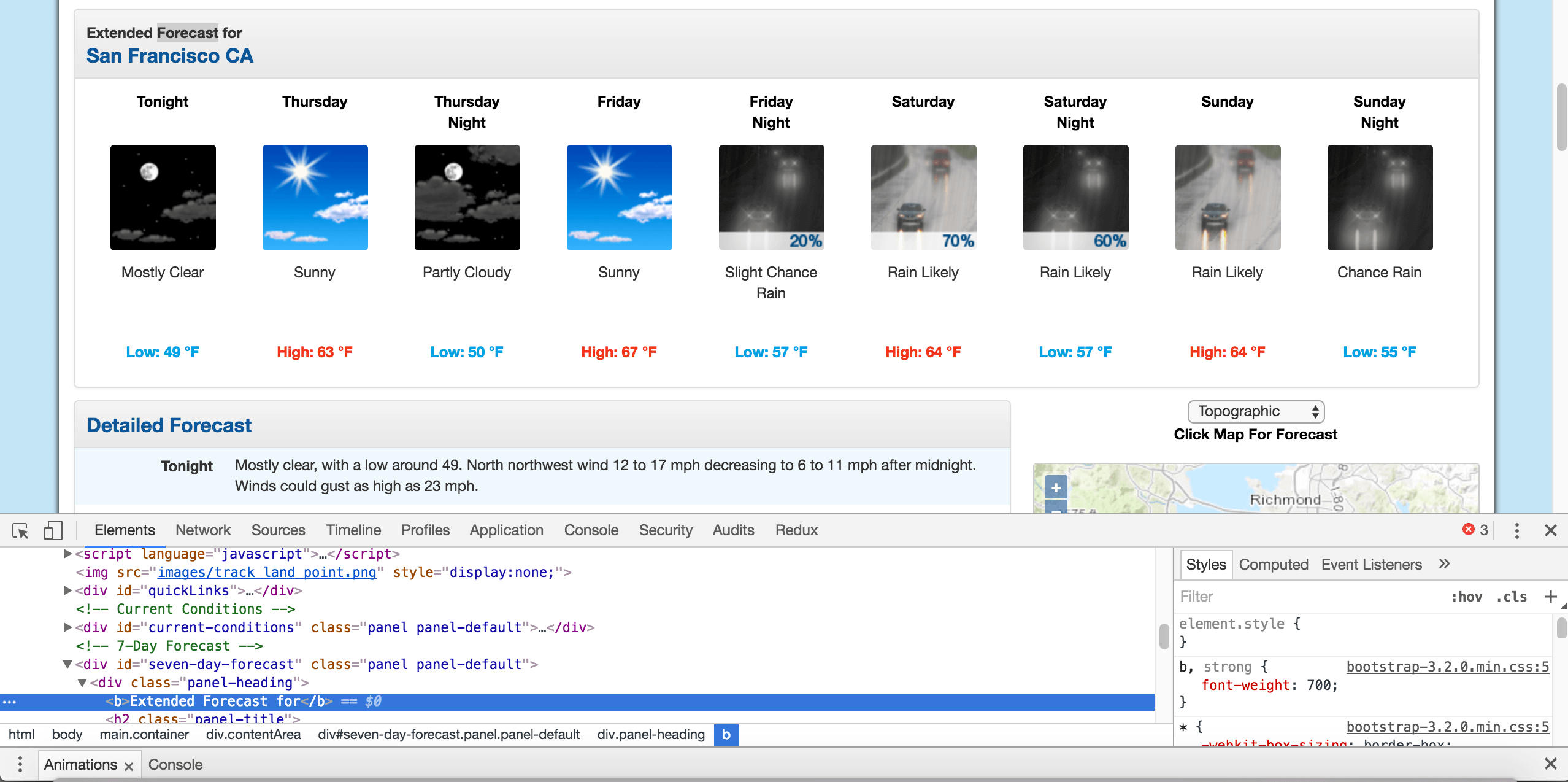

By right clicking on the page near where it says “Extended Forecast”, then clicking “Inspect”, we’ll open up the tag that contains the text “Extended Forecast” in the elements panel:

The extended forecast text

We can then scroll up in the elements panel to find the “outermost” element that contains all of the text that corresponds to the extended forecasts. In this case, it’s a div tag with the id seven-day-forecast:

The div that contains the extended forecast items.

If we click around on the console, and explore the div, we’ll discover that each forecast item (like “Tonight”, “Thursday”, and “Thursday Night”) is contained in a div with the class tombstone-container.

Time to Start Scraping!

We now know enough to download the page and start parsing it. In the below code, we will:

- Download the web page containing the forecast.

- Create a

BeautifulSoupclass to parse the page. - Find the

divwith idseven-day-forecast, and assign toseven_day - Inside

seven_day, find each individual forecast item. - Extract and print the first forecast item.

page = requests.get("https://forecast.weather.gov/MapClick.php?lat=37.7772&lon=-122.4168")

soup = BeautifulSoup(page.content, 'html.parser')

seven_day = soup.find(id="seven-day-forecast")

forecast_items = seven_day.find_all(class_="tombstone-container")

tonight = forecast_items[0]

print(tonight.prettify())<div class="tombstone-container">

<p class="period-name">

Tonight

<br>

<br/>

</br>

</p>

<p>

<img alt="Tonight: Mostly clear, with a low around 49. West northwest wind 12 to 17 mph decreasing to 6 to 11 mph after midnight. Winds could gust as high as 23 mph. " class="forecast-icon" src="newimages/medium/nfew.png" title="Tonight: Mostly clear, with a low around 49. West northwest wind 12 to 17 mph decreasing to 6 to 11 mph after midnight. Winds could gust as high as 23 mph. "/>

</p>

<p class="short-desc">

Mostly Clear

</p>

<p class="temp temp-low">

Low: 49 °F

</p>

</div>Extracting information from the page

As we can see, inside the forecast item tonight is all the information we want. There are four pieces of information we can extract:

- The name of the forecast item — in this case,

Tonight. - The description of the conditions — this is stored in the

titleproperty ofimg. - A short description of the conditions — in this case,

Mostly Clear. - The temperature low — in this case,

49degrees.

We’ll extract the name of the forecast item, the short description, and the temperature first, since they’re all similar:

period = tonight.find(class_="period-name").get_text()

short_desc = tonight.find(class_="short-desc").get_text()

temp = tonight.find(class_="temp").get_text()

print(period)

print(short_desc)

print(temp)Tonight

Mostly Clear

Low: 49 °FNow, we can extract the title attribute from the img tag. To do this, we just treat the BeautifulSoup object like a dictionary, and pass in the attribute we want as a key:

img = tonight.find("img")

desc = img['title']

print(desc)Tonight: Mostly clear, with a low around 49. West northwest wind 12 to 17 mph decreasing to 6 to 11 mph after midnight. Winds could gust as high as 23 mph.Extracting all the information from the page

Now that we know how to extract each individual piece of information, we can combine our knowledge with CSS selectors and list comprehensions to extract everything at once.

In the below code, we will:

- Select all items with the class

period-nameinside an item with the classtombstone-containerinseven_day. - Use a list comprehension to call the

get_textmethod on eachBeautifulSoupobject.

period_tags = seven_day.select(".tombstone-container .period-name")

periods = [pt.get_text() for pt in period_tags]

periods['Tonight',

'Thursday',

'ThursdayNight',

'Friday',

'FridayNight',

'Saturday',

'SaturdayNight',

'Sunday',

'SundayNight']As we can see above, our technique gets us each of the period names, in order.

We can apply the same technique to get the other three fields:

short_descs = [sd.get_text() for sd in seven_day.select(".tombstone-container .short-desc")]

temps = [t.get_text() for t in seven_day.select(".tombstone-container .temp")]

descs = [d["title"] for d in seven_day.select(".tombstone-container img")]print(short_descs)print(temps)print(descs)['Mostly Clear', 'Sunny', 'Mostly Clear', 'Sunny', 'Slight ChanceRain', 'Rain Likely', 'Rain Likely', 'Rain Likely', 'Chance Rain']

['Low: 49 °F', 'High: 63 °F', 'Low: 50 °F', 'High: 67 °F', 'Low: 57 °F', 'High: 64 °F', 'Low: 57 °F', 'High: 64 °F', 'Low: 55 °F']

['Tonight: Mostly clear, with a low around 49. West northwest wind 12 to 17 mph decreasing to 6 to 11 mph after midnight. Winds could gust as high as 23 mph. ', 'Thursday: Sunny, with a high near 63. North wind 3 to 5 mph. ', 'Thursday Night: Mostly clear, with a low around 50. Light and variable wind becoming east southeast 5 to 8 mph after midnight. ', 'Friday: Sunny, with a high near 67. Southeast wind around 9 mph. ', 'Friday Night: A 20 percent chance of rain after 11pm. Partly cloudy, with a low around 57. South southeast wind 13 to 15 mph, with gusts as high as 20 mph. New precipitation amounts of less than a tenth of an inch possible. ', 'Saturday: Rain likely. Cloudy, with a high near 64. Chance of precipitation is 70%. New precipitation amounts between a quarter and half of an inch possible. ', 'Saturday Night: Rain likely. Cloudy, with a low around 57. Chance of precipitation is 60%.', 'Sunday: Rain likely. Cloudy, with a high near 64.', 'Sunday Night: A chance of rain. Mostly cloudy, with a low around 55.']Combining our data into a Pandas Dataframe

We can now combine the data into a Pandas DataFrame and analyze it. A DataFrame is an object that can store tabular data, making data analysis easy. If you want to learn more about Pandas, check out our free to start course here.

In order to do this, we’ll call the DataFrame class, and pass in each list of items that we have. We pass them in as part of a dictionary.

Each dictionary key will become a column in the DataFrame, and each list will become the values in the column:

import pandas as pd

weather = pd.DataFrame({

"period": periods,

"short_desc": short_descs,

"temp": temps,

"desc":descs

})

weather| desc | period | short_desc | temp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tonight: Mostly clear, with a low around 49. W… | Tonight | Mostly Clear | Low: 49 °F |

| 1 | Thursday: Sunny, with a high near 63. North wi… | Thursday | Sunny | High: 63 °F |

| 2 | Thursday Night: Mostly clear, with a low aroun… | ThursdayNight | Mostly Clear | Low: 50 °F |

| 3 | Friday: Sunny, with a high near 67. Southeast … | Friday | Sunny | High: 67 °F |

| 4 | Friday Night: A 20 percent chance of rain afte… | FridayNight | Slight ChanceRain | Low: 57 °F |

| 5 | Saturday: Rain likely. Cloudy, with a high ne… | Saturday | Rain Likely | High: 64 °F |

| 6 | Saturday Night: Rain likely. Cloudy, with a l… | SaturdayNight | Rain Likely | Low: 57 °F |

| 7 | Sunday: Rain likely. Cloudy, with a high near… | Sunday | Rain Likely | High: 64 °F |

| 8 | Sunday Night: A chance of rain. Mostly cloudy… | SundayNight | Chance Rain | Low: 55 °F |

We can now do some analysis on the data. For example, we can use a regular expression and the Series.str.extract method to pull out the numeric temperature values:

temp_nums = weather["temp"].str.extract("(?Pd+)", expand=False)

weather["temp_num"] = temp_nums.astype('int')

temp_nums0 49

1 63

2 50

3 67

4 57

5 64

6 57

7 64

8 55

Name: temp_num, dtype: objectWe could then find the mean of all the high and low temperatures:

weather["temp_num"].mean()58.444444444444443We could also only select the rows that happen at night:

is_night = weather["temp"].str.contains("Low")

weather["is_night"] = is_night

is_night0 True

1 False

2 True

3 False

4 True

5 False

6 True

7 False

8 True

Name: temp, dtype: boolweather[is_night]0 True

1 False

2 True

3 False

4 True

5 False

6 True

7 False

8 True

Name: temp, dtype: bool| desc | period | short_desc | temp | temp_num | is_night | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tonight: Mostly clear, with a low around 49. W… | Tonight | Mostly Clear | Low: 49 °F | 49 | True |

| 2 | Thursday Night: Mostly clear, with a low aroun… | ThursdayNight | Mostly Clear | Low: 50 °F | 50 | True |

| 4 | Friday Night: A 20 percent chance of rain afte… | FridayNight | Slight ChanceRain | Low: 57 °F | 57 | True |

| 6 | Saturday Night: Rain likely. Cloudy, with a l… | SaturdayNight | Rain Likely | Low: 57 °F | 57 | True |

| 8 | Sunday Night: A chance of rain. Mostly cloudy… | SundayNight | Chance Rain | Low: 55 °F | 55 | True |

Next Steps For This Web Scraping Project

If you’ve made it this far, congratulations! You should now have a good understanding of how to scrape web pages and extract data. Of course, there’s still a lot more to learn!

If you want to go further, a good next step would be to pick a site and try some web scraping on your own. Some good examples of data to scrape are:

- News articles

- Sports scores

- Weather forecasts

- Stock prices

- Online retailer prices

You may also want to keep scraping the National Weather Service, and see what other data you can extract from the page, or about your own city.

Alternatively, if you want to take your web scraping skills to the next level, you can check out our interactive course, which covers both the basics of web scraping and using Python to connect to APIs. With those two skills under your belt, you’ll be able to collect lots of unique and interesting datasets from sites all over the web!